Why aren't there more part-time positions in academia?

I left academia for a year, and it changed how I think about the 'leaky pipeline' in STEM. This blog post is a data-supported rant I wrote right before returning back to a post doc position after a one-year hiatus.

Last year, on September 30, 2020, I left my postdoctoral research position. I had decided that a career as a Full Professor wasn’t what I dreamed it would be, and I was exhausted from experiencing or reading about all the social biases that often lead women to leave STEM careers. I applied for a dozen or so jobs in education and industry, but I wasn’t offered any positions. Like many other women, I “leaked out” of the STEM pipeline. For one year, exactly. On October 1, 2021, I officially re-joined Titus Brown’s lab to work on training efforts for the Common Fund Data Ecosystem. Since I took a year off, I thought I would write a short post about what I’ve been doing and thinking about this past year.

I wasn’t able to acquire a “real job” during the pandemic, but I did find seasonal employment. In the winter I worked at a ski resort parking cars before sunrise during snowstorms (left photo). This summer I worked at a landscaping company driving forklifts and front-loaders to move rocks and soil (right photo). I got quite a lot of “you’re pretty good for a girl” comments, which was frustrating there were plenty of women performing these “manly” tasks quite well.

Photos of me parking cars in a snowstorm at sunrise and of the front-loaders I learned how to operate.

Photos of me parking cars in a snowstorm at sunrise and of the front-loaders I learned how to operate.

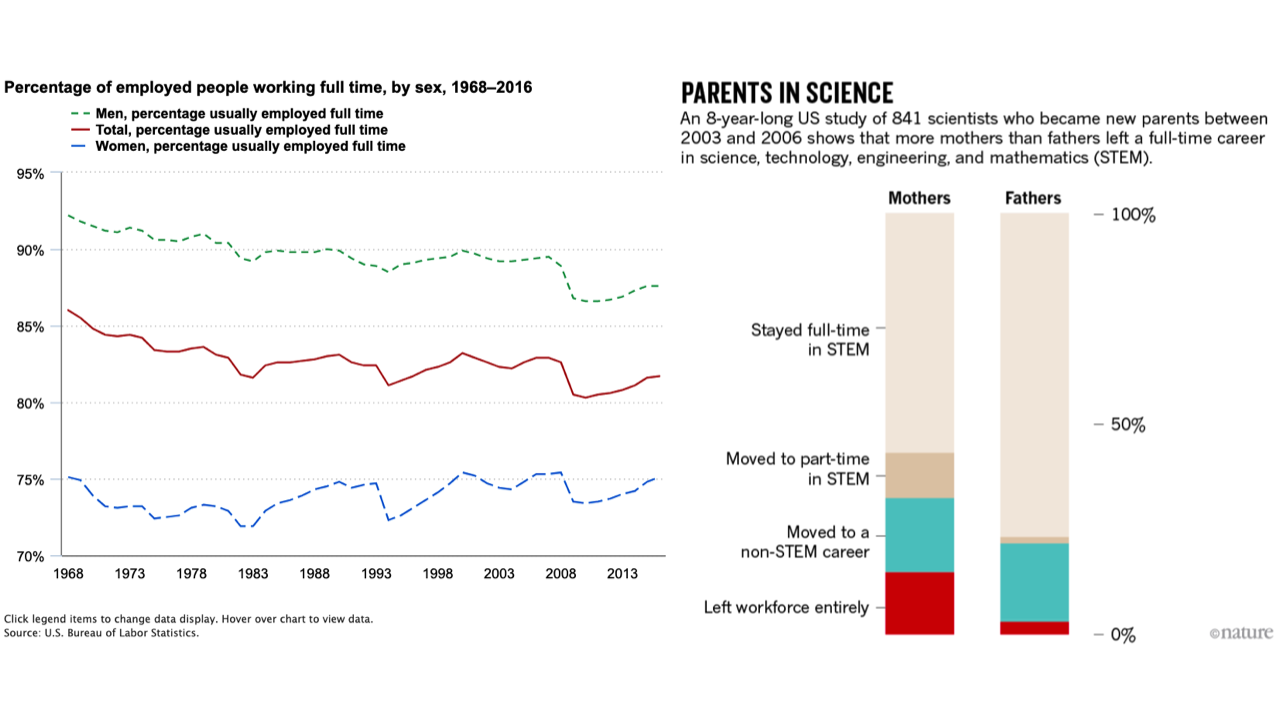

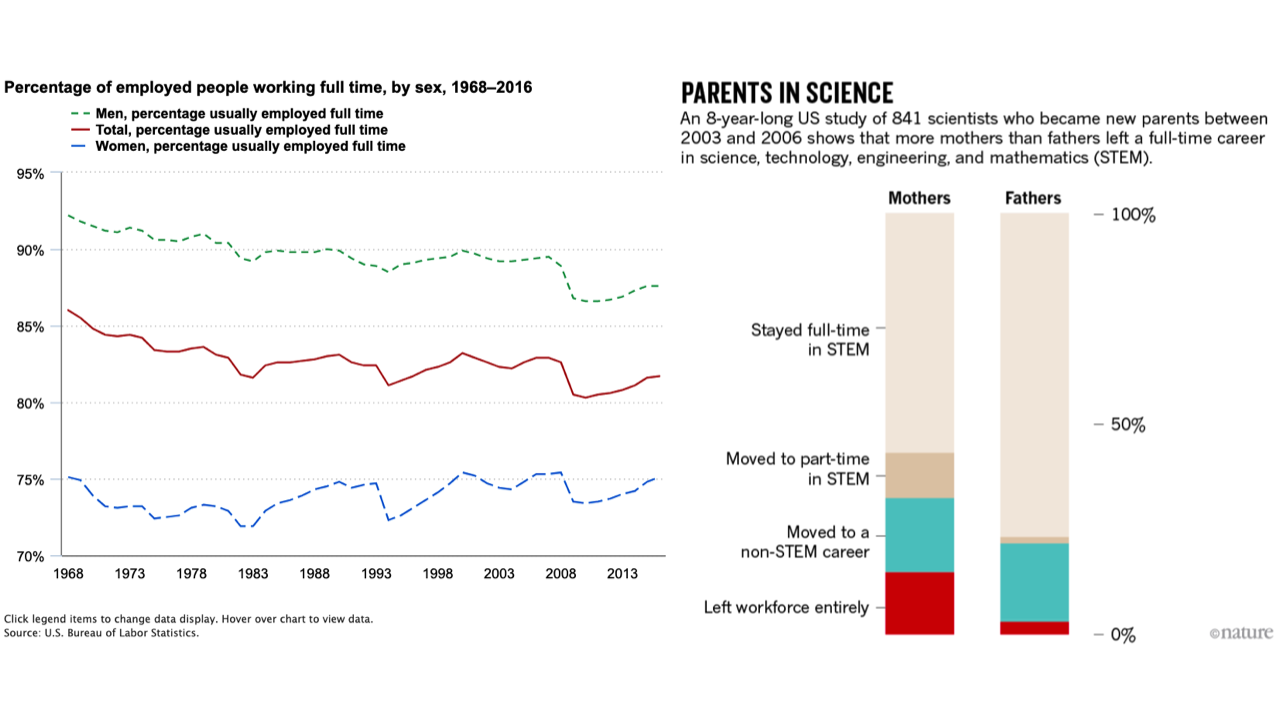

Like science and technology, the skiing industry is male-dominated. Most days at work, it appeared that men outnumbered women 5:1. I wasn’t surprised by this, nor was I surprised to learn that most leadership positions were held by men. I was, however, surprised by the gender differences in hours worked. Most of my female colleagues, especially those with children, opted to work part-time or reduced hours, whereas the men were more likely to pick up overtime shifts to make more money when given the option. I did a little googling and discovered that, for the last 50 years, only about 75% of working women hold full-time jobs, whereas 90% of working men hold full-time jobs (Figure 1, left) [1]. The general interpretation is that men work more to make more money and women work less to provide family care.

Figure 1: For the past 50 years, only about 75% of the female workforce has been employed at full time compared to 90% of men 1.. Mothers are more likely to pursue part-time work following childcare than fathers 2. Why not create more part-time positions all along the STEM pipeline to prevent females from leaking out?

Figure 1: For the past 50 years, only about 75% of the female workforce has been employed at full time compared to 90% of men 1.. Mothers are more likely to pursue part-time work following childcare than fathers 2. Why not create more part-time positions all along the STEM pipeline to prevent females from leaking out?

In an industry where people are paid close to minimum wage, overtime pay is how you make enough to survive. I worked as much overtime as possible for the extra pay, but I could never shake the feeling that working one person overtime was less efficient than working two people part-time. Let’s do some math and say that a position has an hourly wage of $100, including benefits. If a man works 40 hours at $100/hr and 20 hours at ‘time and a half’ or $150/hr, his weekly pay is $7000. However, two women each work 30 hours at regular pay, their combined take home is $6000. The means the employer would save $1000 per week! Also, I find that people make more mistakes when they are overworked, and it can take a toll on their well-being. In today’s economy where unemployment is on the rise and women are increasingly taking on childcare roles, creating more part-time jobs seems like a good solution to me.

In academia, the prestigious positions are salaried, often with the social pressure to work 40-60 hours a week. Many men and women pursue these positions, but after childbirth, women are much more likely to opt for a part-time position than men (Figure 1, right) [2]. One problem with that is that all the prestigious positions are full-time, so taking a part-time job means a loss of power/respect/opportunity/pay/etc. Which makes me wonder, why can’t we create more part-time opportunities that are as equally prestigious as the current full-time opportunities? Like, offer 3-year fellowships where the stipend can be spread across 5 years? Or advertise positions for postdocs and professors that are split between two people working part-time? I think that options like these could help keep more women, especially mothers, in the academic pipeline.

I mentioned this idea for part-time postdocs and professors to a friend and they said something like “but continuity is important and people don’t always work together”. This is true, but I think those can be resolved with good project management. Another colleague told me that visiting international scholars would not be eligible for visas if they worked part-time, so there are some institutional barriers that might be hard to change.

Anyways, what are your thoughts? Are part-time postdocs a potential solution to the leaky academic pipeline? If so, how can we make them a thing? If not, what other solutions do you have?

References

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2017/percentage-of-employed-women-working-full-time-little-changed-over-past-5-decades.htm

- Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00611-1